Parametric oscillator

A parametric oscillator is a harmonic oscillator whose parameters oscillate in time. For example, a well known parametric oscillator is a child pumping a swing by periodically standing and squatting to increase the size of the swing's oscillations.[1][2][3] The varying of the parameters drives the system. Examples of parameters that may be varied are its resonance frequency  and damping

and damping  .

.

Parametric oscillators are used in many applications. The classical varactor parametric oscillator will oscillate when the diode's capacitance is varied periodically. The circuit that varies the diode's capacitance is called the "pump" or "driver". In microwave electronics, waveguide/YAG based parametric oscillators operate in the same fashion. The designer varies a parameter periodically in order to induce oscillations.

Parametric oscillators have been developed as low-noise amplifiers, especially in the radio and microwave frequency range. Thermal noise is minimal, since a reactance (not a resistance) is varied. Another common use is frequency conversion, e.g., conversion from audio to radio frequencies. For example, the Optical parametric oscillator converts an input laser wave into two output waves of lower frequency ( ).

).

Parametric resonance occurs in a mechanical system when a system is parametrically excited and oscillates at one of its resonant frequencies. Parametric excitation differs from forcing since the action appears as a time varying modification on a system parameter. This effect is different from regular resonance because it exhibits the instability phenomenon.

Contents |

History

Michael Faraday (1831) was the first to notice oscillations of one frequency being excited by forces of double the frequency, in the crispations (ruffled surface waves) observed in a wine glass excited to "sing".[4] Melde (1859) generated parametric oscillations in a string by employing a tuning fork to periodically vary the tension at twice the resonance frequency of the string.[5] Parametric oscillation was first treated as a general phenomenon by Rayleigh (1883,1887), whose papers are still worth reading today.[6][7][8]

Parametric amplifiers (paramps) were first used in 1913-1915 for radio telephony from Berlin to Vienna and Moscow, and were predicted to have a useful future (Ernst Alexanderson, 1916).[9] The early paramps varied inductances, but other methods have been developed since, e.g., the varactor diodes, klystron tubes, Josephson junctions and optical methods.

The mathematics

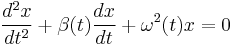

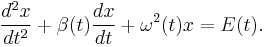

This equation is linear in  . By assumption, the parameters

. By assumption, the parameters  and

and  depend only on time and do not depend on the state of the oscillator. In general,

depend only on time and do not depend on the state of the oscillator. In general,  and/or

and/or  are assumed to vary periodically, with the same period

are assumed to vary periodically, with the same period  .

.

Remarkably, if the parameters vary at roughly twice the natural frequency of the oscillator (defined below), the oscillator phase-locks to the parametric variation and absorbs energy at a rate proportional to the energy it already has. Without a compensating energy-loss mechanism provided by  , the oscillation amplitude grows exponentially. (This phenomenon is called parametric excitation, parametric resonance or parametric pumping.) However, if the initial amplitude is zero, it will remain so; this distinguishes it from the non-parametric resonance of driven simple harmonic oscillators, in which the amplitude grows linearly in time regardless of the initial state.

, the oscillation amplitude grows exponentially. (This phenomenon is called parametric excitation, parametric resonance or parametric pumping.) However, if the initial amplitude is zero, it will remain so; this distinguishes it from the non-parametric resonance of driven simple harmonic oscillators, in which the amplitude grows linearly in time regardless of the initial state.

A familiar experience of both parametric and driven oscillation is playing on a swing.[1][2][3] Rocking back and forth pumps the swing as a driven harmonic oscillator, but once moving, the swing can also be parametrically driven by alternately standing and squatting at key points in the swing. This changes moment of inertia of the swing and hence the resonance frequency, and children can quickly reach large amplitudes provided that they have some amplitude to start with (e.g., get a push). Standing and squatting at rest, however, goes nowhere.

Transformation of the equation

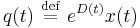

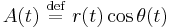

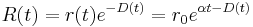

We begin by making a change of variables

where  is a time integral of the damping

is a time integral of the damping

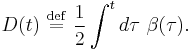

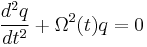

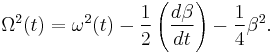

This change of variables eliminates the damping term

where the transformed frequency is defined

In general, the variations in damping and frequency are relatively small perturbations

where  and

and  are constants, namely, the time-averaged oscillator frequency and damping, respectively. The transformed frequency can be written in a similar way:

are constants, namely, the time-averaged oscillator frequency and damping, respectively. The transformed frequency can be written in a similar way:

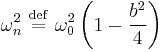

where  is the natural frequency of the damped harmonic oscillator

is the natural frequency of the damped harmonic oscillator

and

Thus, our transformed equation can be written

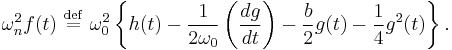

Remarkably, the independent variations  and

and  in the oscillator damping and resonance frequency, respectively, can be combined into a single pumping function

in the oscillator damping and resonance frequency, respectively, can be combined into a single pumping function  . The converse conclusion is that any form of parametric excitation can be accomplished by varying either the resonance frequency or the damping, or both.

. The converse conclusion is that any form of parametric excitation can be accomplished by varying either the resonance frequency or the damping, or both.

Solution of the transformed equation

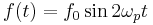

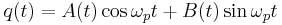

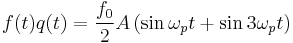

Let us assume that  is sinusoidal, specifically

is sinusoidal, specifically

where the pumping frequency  but need not equal

but need not equal  exactly. The solution

exactly. The solution  of our transformed equation may be written

of our transformed equation may be written

where we have factored out the rapidly varying components ( and

and  ) to isolate the slowly varying amplitudes

) to isolate the slowly varying amplitudes  and

and  . This corresponds to Laplace's variation of parameters method.

. This corresponds to Laplace's variation of parameters method.

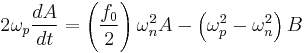

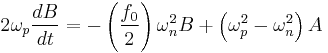

Substituting this solution into the transformed equation and retaining only the terms first-order in  yields two coupled equations

yields two coupled equations

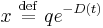

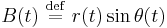

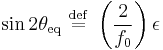

We may decouple and solve these equations by making another change of variables

which yields the equations

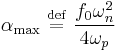

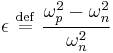

where we have defined for brevity

and the detuning

The  equation does not depend on

equation does not depend on  , and linearization near its equilibrium position

, and linearization near its equilibrium position  shows that

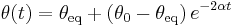

shows that  decays exponentially to its equilibrium

decays exponentially to its equilibrium

where the decay constant

.

.

In other words, the parametric oscillator phase-locks to the pumping signal  .

.

Taking  (i.e., assuming that the phase has locked), the

(i.e., assuming that the phase has locked), the  equation becomes

equation becomes

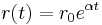

whose solution is  ; the amplitude of the

; the amplitude of the  oscillation diverges exponentially. However, the corresponding amplitude

oscillation diverges exponentially. However, the corresponding amplitude  of the untransformed variable

of the untransformed variable  need not diverge

need not diverge

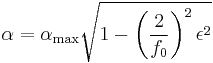

The amplitude  diverges, decays or stays constant, depending on whether

diverges, decays or stays constant, depending on whether  is greater than, less than, or equal to

is greater than, less than, or equal to  , respectively.

, respectively.

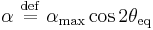

The maximum growth rate of the amplitude occurs when  . At that frequency, the equilibrium phase

. At that frequency, the equilibrium phase  is zero, implying that

is zero, implying that  and

and  . As

. As  is varied from

is varied from  ,

,  moves away from zero and

moves away from zero and  , i.e., the amplitude grows more slowly. For sufficiently large deviations of

, i.e., the amplitude grows more slowly. For sufficiently large deviations of  , the decay constant

, the decay constant  can become purely imaginary since

can become purely imaginary since

If the detuning  exceeds

exceeds  ,

,  becomes purely imaginary and

becomes purely imaginary and  varies sinusoidally. Using the definition of the detuning

varies sinusoidally. Using the definition of the detuning  , the pumping frequency

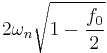

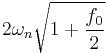

, the pumping frequency  must lie between

must lie between  and

and  in order to achieve exponetial growth in

in order to achieve exponetial growth in  . Expanding the square roots in a binomial series shows that the spread in pumping frequencies that result in exponentially growing

. Expanding the square roots in a binomial series shows that the spread in pumping frequencies that result in exponentially growing  is approximately

is approximately  .

.

Intuitive derivation of parametric excitation

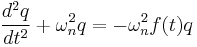

The above derivation may seem like a mathematical sleight-of-hand, so it may be helpful to give an intuitive derivation. The  equation may be written in the form

equation may be written in the form

which represents a simple harmonic oscillator (or, alternatively, a bandpass filter) being driven by a signal  that is proportional to its response

that is proportional to its response  .

.

Assume that  already has an oscillation at frequency

already has an oscillation at frequency  and that the pumping

and that the pumping  has double the frequency and a small amplitude

has double the frequency and a small amplitude  . Applying a trigonometric identity for products of sinusoids, their product

. Applying a trigonometric identity for products of sinusoids, their product  produces two driving signals, one at frequency

produces two driving signals, one at frequency  and the other at frequency

and the other at frequency

Being off-resonance, the  signal is attentuated and can be neglected initially. By contrast, the

signal is attentuated and can be neglected initially. By contrast, the  signal is on resonance, serves to amplify

signal is on resonance, serves to amplify  and is proportional to the amplitude

and is proportional to the amplitude  . Hence, the amplitude of

. Hence, the amplitude of  grows exponentially unless it is initially zero.

grows exponentially unless it is initially zero.

Expressed in Fourier space, the multiplication  is a convolution of their Fourier transforms

is a convolution of their Fourier transforms  and

and  . The positive feedback arises because the

. The positive feedback arises because the  component of

component of  converts the

converts the  component of

component of  into a driving signal at

into a driving signal at  , and vice versa (reverse the signs). This explains why the pumping frequency must be near

, and vice versa (reverse the signs). This explains why the pumping frequency must be near  , twice the natural frequency of the oscillator. Pumping at a grossly different frequency would not couple (i.e., provide mutual positive feedback) between the

, twice the natural frequency of the oscillator. Pumping at a grossly different frequency would not couple (i.e., provide mutual positive feedback) between the  and

and  components of

components of  .

.

Parametric resonance

Parametric resonance is the parametrical resonance phenomenon of mechanical excitation and oscillation at certain frequencies (and the associated harmonics). This effect is different from regular resonance because it exhibits the instability phenomenon.

Parametric resonance occurs in a mechanical system when a system is parametrically excited and oscillates at one of its resonant frequencies.Parametric resonance takes place when the external excitation frequency equals to twice the natural frequency of the system. Parametric excitation differs from forcing since the action appears as a time varying modification on a system parameter. The classical example of parametric resonance is that of the vertically forced pendulum.

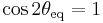

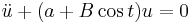

For small amplitudes and by linearising, the stability of the periodic solution is given by :

where  is some perturbation from the periodic solution. Here the

is some perturbation from the periodic solution. Here the  term acts as an ‘energy’ source and is said to parametrically excite the system. The Mathieu equation describes many other physical systems to a sinusoidal parametric excitation such as an LC Circuit where the capacitor plates move sinusoidally.

term acts as an ‘energy’ source and is said to parametrically excite the system. The Mathieu equation describes many other physical systems to a sinusoidal parametric excitation such as an LC Circuit where the capacitor plates move sinusoidally.

Parametric amplifiers

Introduction

A parametric amplifier is implemented as a mixer. The mixer's gain shows up in the output as amplifier gain. The input weak signal is mixed with a strong local oscillator signal, and the resultant strong output is used in the ensuing receiver stages.

Parametric amplifiers also operate by changing a parameter of the amplifier. Intuitively, this can be understood as follows, for a variable capacitor based amplifier.

Q [charge in a capacitor] = C x V

therefore

V [voltage across a capacitor] = Q/C

Knowing the above, if a capacitor is charged until its voltage equals the sampled voltage of an incoming weak signal, and if the capacitor's capacitance is then reduced (say, by manually moving the plates further apart), then the voltage across the capacitor will increase. In this way, the voltage of the weak signal is amplified.

If the capacitor is a varicap diode, then the 'moving the plates' can be done simply by applying time-varying DC voltage to the varicap diode. This driving voltage usually comes from another oscillator — sometimes called a "pump".

The resulting output signal contains frequencies that are the sum and difference of the input signal (f1) and the pump signal (f2): (f1 + f2) and (f1 - f2).

A practical parametric oscillator needs the following connections: one for the "common" or "ground", one to feed the pump, one to retrieve the output, and maybe a fourth one for biasing. A parametric amplifier needs a fifth port to input the signal being amplified. Since a varactor diode has only two connections, it can only be a part of an LC network with four eigenvectors with nodes at the connections. This can be implemented as a transimpedance amplifier, a traveling wave amplifier or by means of a circulator.

Mathematical equation

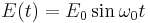

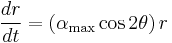

The parametric oscillator equation can be extended by adding an external driving force  :

:

We assume that the damping  is sufficiently strong that, in the absence of the driving force

is sufficiently strong that, in the absence of the driving force  , the amplitude of the parametric oscillations does not diverge, i.e., that

, the amplitude of the parametric oscillations does not diverge, i.e., that  . In this situation, the parametric pumping acts to lower the effective damping in the system. For illustration, let the damping be constant

. In this situation, the parametric pumping acts to lower the effective damping in the system. For illustration, let the damping be constant  and assume that the external driving force is at the mean resonance frequency

and assume that the external driving force is at the mean resonance frequency  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  . The equation becomes

. The equation becomes

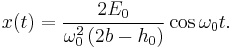

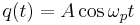

whose solution is roughly

As  approaches the threshold

approaches the threshold  , the amplitude diverges. When

, the amplitude diverges. When  , the system enters parametric resonance and the amplitude begins to grow exponentially, even in the absence of a driving force

, the system enters parametric resonance and the amplitude begins to grow exponentially, even in the absence of a driving force  .

.

Advantages

1:It is highly sensitive.

2:low noise level amplifier for ultra high frequency and microwave radio signal.

Other relevant mathematical results

If the parameters of any second-order linear differential equation are varied periodically, Floquet analysis shows that the solutions must vary either sinusoidally or exponentially.

The  equation above with periodically varying

equation above with periodically varying  is an example of a Hill equation. If

is an example of a Hill equation. If  is a simple sinusoid, the equation is called a Mathieu equation.

is a simple sinusoid, the equation is called a Mathieu equation.

See also

References

- ^ a b Case, William. "Two ways of driving a child's swing". http://www.grinnell.edu/academic/physics/faculty/case/swing/. Retrieved 27 November 2011. Note: In real-life playgrounds, swings are predominantly driven, not parametric, oscillators.

- ^ a b Case, W. B. (1996). "The pumping of a swing from the standing position". American Journal of Physics 64: 215-220.

- ^ a b Roura, P.; Gonzalez, J.A. (2010). "Towards a more realistic description of swing pumping due to the exchange of angular momentum". European Journal of Physics 31: 1195-1207.

- ^ Faraday, M. (1831) "On a peculiar class of acoustical figures; and on certain forms assumed by a group of particles upon vibrating elastic surfaces", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (London), vol. 121, pages 299-318.

- ^ Melde, F. (1859) "Über Erregung stehender Wellen eines fadenförmigen Körpers" [On the excitation of standing waves on a string], Annalen der Physik und Chemie (Ser. 2), vol. 109, pages 193-215.

- ^ Strutt, J.W. (Lord Rayleigh) (1883) "On maintained vibrations", Philosophical Magazine, vol. 15, pages 229-235.

- ^ Strutt, J.W. (Lord Rayleigh) (1887) "On the maintenance of vibrations by forces of double frequency, and on the propagation of waves through a medium endowed with periodic structure", Philosophical Magazine, vol.24, pages 145-159.

- ^ Strutt, J.W. (Lord Rayleigh) The Theory of Sound, 2nd. ed. (N.Y., N.Y.: Dover, 1945), vol. 1, pages 81-85.

- ^ Alexanderson, Ernst F.W. (April 1916) "A magnetic amplifier for audio telephony" Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers, vol. 4, pages 101-149.

Further reading

- Kühn L. (1914) Elektrotech. Z., 35, 816-819.

- Mumford WW. (1960) "Some Notes on the History of Parametric Transducers", Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers, 48, 848-853.

- Pungs L. DRGM Nr. 588 822 (24 October 1913); DRP Nr. 281440 (1913); Elektrotech. Z., 44, 78-81 (1923?); Proc. IRE, 49, 378 (1961).

External articles

- Elmer, Franz-Josef, "Parametric Resonance". unibas.ch, July 20, 1998.

- Cooper, Jeffery, "Parametric Resonance in Wave Equations with a Time-Periodic Potential". SIAM Journal on Mathematical Analysis, Volume 31, Number 4, pp. 821–835. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 2000 .

- "Driven Pendulum: Parametric Resonance". phys.cmu.edu (Demonstration of physical mechanics or classical mechanics. Resonance oscillations set up in a simple pendulum via periodically varying pendulum length.)

![\beta(t) = \omega_{0} \left[b %2B g(t) \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a500571dda33de1e914f6b68552f1513.png)

![\omega^{2}(t) = \omega_{0}^{2} \left[1 %2B h(t) \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/223f5f87d0341aefe7f7ea19c98631c3.png)

![\Omega^{2}(t) = \omega_{n}^{2} \left[1 %2B f(t) \right],](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c7aa2ce35449f8b3ef28f3a7500adf6a.png)

![\frac{d^{2}q}{dt^{2}} %2B \omega_{n}^{2} \left[1 %2B f(t) \right] q = 0.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/90fba4c9c6dd6723657677e09a32eab9.png)

![\frac{d\theta}{dt} = -\alpha_{\mathrm{max}}

\left[\sin 2\theta - \sin 2\theta_{\mathrm{eq}} \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/02bb47c33485a9c3b8e42e917d06d05a.png)

![\frac{d^{2}x}{dt^{2}} %2B b \omega_{0} \frac{dx}{dt} %2B

\omega_{0}^{2} \left[1 %2B h_{0} \sin 2\omega_{0} t \right] x =

E_{0} \sin \omega_{0} t](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fa57d94cc78a9cf77a640a2d9349eedb.png)